The World Adaptation Forum, to which our researcher Íñigo Capellán Pérez was invited, was held in Budapest on 25 April. Following his intervention at the meeting, Íñigo shares his reflections on societal collapse in this post:

The invitation. Crash course on collapsology

Last summer I was invited to participate as a speaker to a quite unconventional event: the World Adaptation Forum (WAF) 2025, the second edition of a public outreach conference about the risk and consequences of “societal collapse”, organized by the Hungarian organization https://cassandraprogram.hu/. It was the first time I had heard of the ‘Deep Adaptation’ movement, originally initiated by the controversial Jem Bendell in 2018, although the topic of societal collapse is much broader than that. Not to confound with “adaptation” as usually used in climate science (eg., IPCC WG2), the Deep Adaptation movement is a global framework and community that supports emotional and practical adaptation to anticipated societal collapse from climate and environmental crises.

In popular culture, collapse is often imagined as a sudden, violent event: the fall of empires, total chaos, looting, war, and the end of order. People fear a return to a primitive life, with isolated, desperate survivors and no technology or culture. This likely explains why the term often provokes an immediate, instinctive—and understandable—resistance.

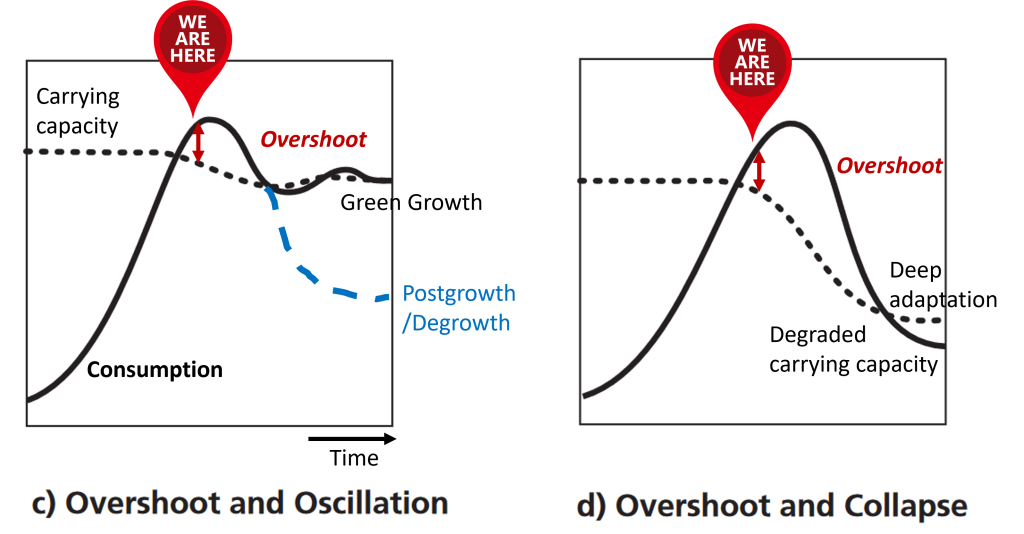

In scientific discourse, the concept of societal collapse is usually put up in a more structural definition: a process through which a society experiences a rapid and substantial reduction in sociopolitical complexity (e.,g (Tainter, 1990)). This means it is not deterministic/predictive regarding its processes and outcomes. It carries no inherent assumptions about the severity of suffering, poverty, or mortality involved, nor does it preclude the potential for “better” systems to arise from collapse. Both violence and/or impoverishment are context-dependent. ‘Overeshoot and collapse’ as potential endpoint of the current industrial civilization due to resources and/or pollution crises was anticipated by the Limits to Growth report as early as 1972 (Meadows et al., 1972). However, due to the largely unfounded and ideologically driven discrediting of this report (Bardi, 2011), this and other cornerstone concepts of this research fell into oblivion. Today, collapse is predominantly related with the consequences on human societies of environmental degradation of the life-base support systems (eg., (Ripple et al., 2019)), and to a lesser extent with biophysical constraints to human activities (eg., recalibrated World3 (Nebel et al., 2024)), while others focus on the interactions between both types of limits, such as (Crownshaw et al., 2018; Motesharrei et al., 2014) or in our own modelling work simulating MEDEAS (Capellán-Pérez et al., 2020). There is also a recent surge investigating the collapse of past societies, cf. eg., the books from Constanza et al (2007), Bardi (2017) and Middleton (2025).

At the societal level, my perception — reinforced by attending the WAF conference and engaging with participants from various countries — is that the situation varies considerably across countries. In Spain the richness, diversity, and depth of the emerging conversation are truly remarkable. Pioneers were R. Fernandéz Durán y L. González Reyes who published the exceptional public outreach book “En la Espiral de la Energía” in 2014 (now in its 4th edition; and that if is a truly pity it is not translated into English or other languages), the tireless Antonio Turiel (https://crashoil.blogspot.com/) and Ferran Puig Vilar (https://ustednoselocree.com/) or some of my colleagues at GEEDS, among others (the full list would be too long!). There is even a magazine specifically dedicated (15-15-15) and a closely related University Master. In Spain, a growing and vibrant intellectual movement is connecting the challenges of the industrial model with the aspiration to transform its eventual collapse into an opportunity to build a new society inspired by Degrowth principles, while simultaneously acknowledging the associated challenges, threats, and risks (see eg., Manuel Casal Lodeiro response to T. Trainer).

The organizers were interested in the perspective on the biophysical and technical barriers that a Green Growth transition to renewables face (materials, EROI, land, speculative technologies, etc.), a topic we have extensively worked on at GEEDS. As I found the conference topic particularly compelling, as plausible futures involving societal collapse remain underexplored in research and public discourse—despite current trends of inadequate or counterproductive action. As the forum seemed independent, original, engaging and open to diverse perspectives, I accepted the invitation. It was obviously not possible to read all this extensive literature before the conference, but I made an effort to familiarize myself with the public debate in Spain. I found that there is some confusion around certain definitions or basic starting points, sometimes intentionally to muddle the discussion. In fact, the view of the collapse of industrial society as an opportunity for Degrowth has faced fierce opposition, sometimes from a priori unexpected quarters (see for example this post from Antonio Turiel).

With far more questions than answers, but full of curiosity about how the event would unfold I boarded in my train to Budapest.

The Conference. Budapest, 25/04/2025

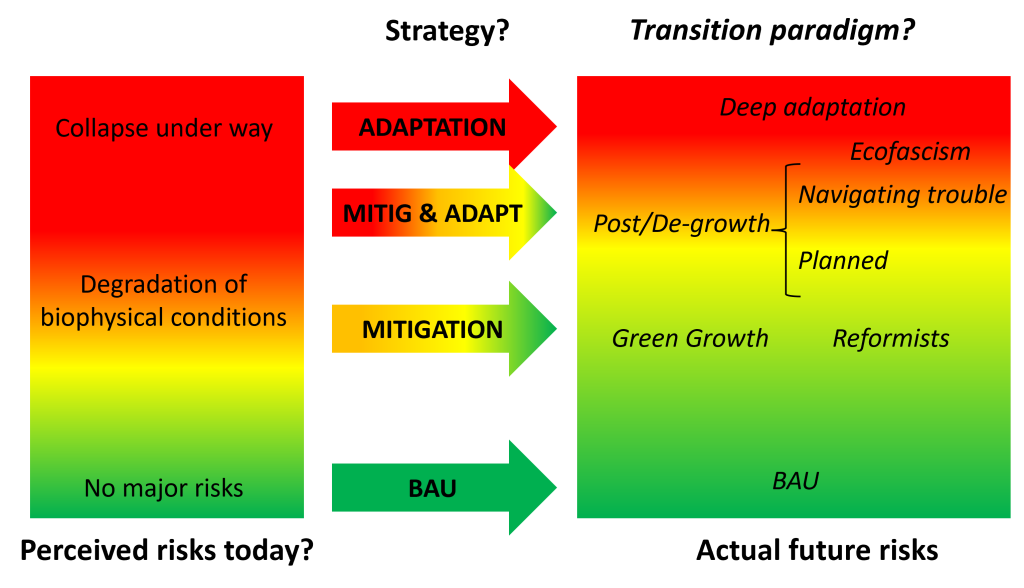

I opened the conference with my presentation about limits and contradictions of the Green Growth strategy [PPT available here]. I started with in my opinion one of the key issues: the totally different perceptions of the current situation. See below the first slide, incorporating Eco-fascism after comments from Ugo Bardi (cf. his post after the conference).

Varying perceptions of risks (affected by different information, biases, media influence, psychological factors, etc.) combine with people values (and all the previous list) to a myriad of transition paradigms. From BAU to ‘Deep Adaptation’, different perspectives about system continuation (Green Growth), with some adjustments (Reformists) and different shades of Post and Degrowth. Within the latter, I distinguished between (1) more planned approaches which require stability in the boundary conditions and (2) what I’ve referred to as ‘navigating trouble’—where the overlapping environmental degradation, weakened governance and democracy make standard planning approaches extremely difficult.

The current state of the debate is that scientific uncertainties (in the line of Post-Normal Science) do not allow to establish if the overshoot situation will be possible to be stabilized in a controlled way at a desired level (GG and planned Postgrowth/Degrowth), or if dynamics already in place will be already too strong to be counteracted (Deep adaptation/collapse), Degrowth “navigating trouble” lying somewhere in between.

I then moved on to the core topic of the presentation, introducing the set of biophysical constraints on future energy pathways based on GEEDS work—such as peak resource limits, techno-sustainable potentials of renewables, EROI, materials availability and limits to technological development—supported by a series of illustrative simulations focused on the materials required for transport electrification and the deployment of electrolytic hydrogen to be used as feedstock. At the end, I briefly shared my perspective on eventual global societal collapse. While I consider a global societal collapse will come if broad current trends—both in the form of BAU or GG—persist, significant uncertainties remain due to gaps in our understanding of the irreversibility of damages and the historical potential for humanity to enact remarkable changes under extreme pressure and challenging circumstances (cf. Dawn of Everything or Humankind. A hopeful history) —though there is no guarantee that such transformations will occur at scale neither in time.

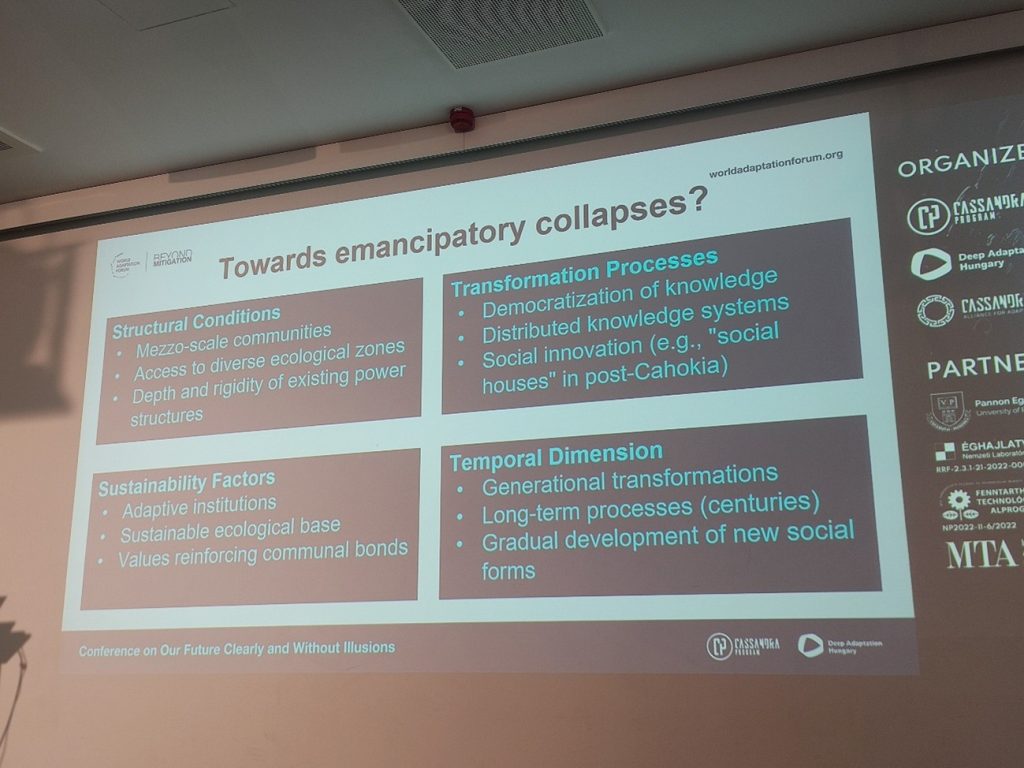

There were very diverse presentations from very different perspectives: more evidence about the polycrisis (energy, materials, biodiversity), a very nice presentation from András Gelencsér about the failures of the System of Science and Technology -highlighting the too common fairytales of technology-and the historical perspective given by Ugo Bardi. Ginie Servant-Mikló brought her experience about Zambia’s drought crisis as a catalyst for social collapse and rising drug abuse, as well as original psychological perspectives. Raphaël Stevens, one of the co-creators of the term “collapsology” with the aforementioned published homonymous book with Pablo Servigne, was in fact one of the few speakers framing the topic focusing on the conditions and possibilities for “emancipatory collapse” through the historical analysis of 2 past societies which managed it (Cahokia and Zomia). Incidentally, if I’m not mistaken, they were the only speaker to provide definitions of collapse-related terms (an issue on which I will come back later).

Personal reflections

Participating in this event was a valuable opportunity to reflect on the often-overlooked but crucial issue of potential societal collapse.

A key source of confusion during the conference was related to the different (too often implicit) interpretations/understandings of some key concepts, standing out what is societal collapse, which specific systems or domains are expected to collapse, what is resilience and its relation with transformativity, etc. Also, the distinction between ‘collapsology’ and ‘collapsism’ is crucial to avoid misunderstandings. “Collapsology” describes a more academic or systematic approach to studying the causes, signs, and potential outcomes of societal collapse. It is less about believing in collapse as inevitable and more about studying and understanding it as a phenomenon, focusing on its interdisciplinary aspects such as ecological, economic, political, and social factors that might contribute to a breakdown of complex systems, and then propose/explore societal responses. On the other hand, “collapsists” focus on the belief or advocacy of collapse, and hence on the communication and preparation to adapt to the worse consequences. Unfortunately, at least in Spain, collapsologists are frequently conflated with collapsists—sometimes deliberately—to discredit their perspectives.

Another source of confusion was the differing views about these issues between countries. I’ve already briefly overviewed the situation in Spain, which appears similar to France’s, while for example in the Netherlands it seems that the topic is consciously avoided, as in the Flemish part of Belgium, which point to the importance of cultural factors. The situation in Hungary also revealed considerable complexity and nuance. As there were significant differences between speakers, it would have been a good idea to have planned debates between speakers in the afternoon, which is something I would recommend for future editions.

After the conference, Ugo Bardi published a post in which, based on his past experience as ‘Peak Oiler’, he raised several concerns about the risks of emphasizing the threat of societal collapse, warning that this could unintentionally fuel eco-fascist tendencies. This is also one of the arguments some critics of collapsology are using in Spain to justify avoiding public alarm or panic. However, in my opinion, this is a false dilemma—avoiding transparent communication with society is itself a first step toward authoritarianism. However, the balance between not falling into catastrophic determinism neither avoiding self-deception is also quite challenging… In any case, as Ginie Servant-Miklós pointed out, any scope should devote substantial time to exploring potential ways to cope with the impacts or possible ways forward after addressing the diagnosis. Despite WAF is designed as an open forum to discuss around societal collapse, in my view the conference program focused excessively on diagnosing problems and lacked an exploration of potential ways to avoid worst-case scenarios, whether through building resilience, system transformation, or mitigation (as mitigation -even if partial can be seen in fact as the most effective adaptation strategy). I missed a presentation focused on De/Postgrowth as the most relevant sustainability counter-narrative to institutional Green Growth—though it’s important to acknowledge that this framework still faces limitations for its operationalization, due to conceptual gaps, feasibility challenges, and a lack of consensus on key issues and strategies, as we explored in recent work (Lauer et al., 2025), see also (Fitzpatrick et al., 2025). These barriers complicate planned transitions, making reactive ‘navigating trouble’ approaches more likely. Therefore, the interaction between DG/PG and collapse risks—especially regarding vulnerabilities and resilience—warrants further research, particularly on its effects on transformational strategies. In summary, I see it as a positive sign that organizations are emerging to coordinate dissemination and guide debates about the risk of societal collapse. However, at the intersection of science and activism, it is crucial that information and data are handled carefully to ensure that discussions about collapse inspire constructive action rather than provoke despair, paralysis, or even give rise to ecofascist ideas. In this context, any critiques of Green Growth must be accompanied by viable positive alternatives. In my view, given current trends, these alternatives should be realistically framed within a De/Post-growth perspective focused on ‘navigating trouble.’ Meanwhile, probably the most challenging societal barrier is widespread media mis- and disinformation, which distances the general public from the most basic concepts needed for such discussions.

Lausanne, May 2025

Acknowledgements

Agradezco a Raphaël Stevens y a mis colegas del GEEDS Carlos de Castro y Marga Mediavilla por sus comentarios a una versión inicial del texto. También agradezco a Julia K. Steinberger y a Szandra Köves por compartir sus reflexiones sobre el tema. Por supuesto, cualquier opinión expresada y los eventuales errores restantes son únicamente míos.

References

*Original title: “Comment tout peut s’effondrer”. Pablo Servigne & Raphaël Stevens. Editions du Seuil (2015). https://www.seuil.com/ouvrage/comment-tout-peut-s-effondrer-pablo-servigne/9782021223316

Conference materials

Bardi, U., 2017. The Seneca Effect: Why Growth is Slow but Collapse is Rapid. Springer.

Bardi, U., 2011. The limits to growth revisited. Springer, New York.

Capellán-Pérez, I., Blas, I. de, Nieto, J., Castro, C. de, Miguel, L.J., Carpintero, Ó., Mediavilla, M., Lobejón, L.F., Ferreras-Alonso, N., Rodrigo, P., Frechoso, F., Álvarez-Antelo, D., 2020. MEDEAS: a new modeling framework integrating global biophysical and socioeconomic constraints. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 986–1017. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9EE02627D

Costanza, R., Graumlich, L., Steffen, W.W.L., 2007. Sustainability Or Collapse?: An Integrated History And Future of People on Earth. MIT Press.

Crownshaw, T., Morgan, C., Adams, A., Sers, M., Britto dos Santos, N., Damiano, A., Gilbert, L., Yahya Haage, G., Horen Greenford, D., 2018. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 2053019618820350. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019618820350

Fitzpatrick, N., Eversberg, D., Schmelzer, M., 2025. Exploring the degrowth movement: A survey of conceptualisations, strategies, and tactics. Energy Research & Social Science 124, 104045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2025.104045

Lauer, A., Capellán-Pérez, I., Wergles, N., 2025. A comparative review of de- and post-growth modeling studies. Ecological Economics 227, 108383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108383

Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L., Randers, J., Behrens III, W.W., 1972. The Limits to Growth. Universe Books, New York (USA).

Meadows, D.H., Randers, J., Meadows, D.L., 2004. The limits to growth: the 30-year update. Chelsea Green Publishing Company, White River Junction, Vt.

Middleton, G.D., 2025. Collapse Studies in Archaeology from 2012 to 2023. J Archaeol Res 33, 57–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-024-09196-4

Motesharrei, S., Rivas, J., Kalnay, E., 2014. Human and nature dynamics (HANDY): Modeling inequality and use of resources in the collapse or sustainability of societies. Ecological Economics 101, 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.02.014

Nebel, A., Kling, A., Willamowski, R., Schell, T., 2024. Recalibration of limits to growth: An update of the World3 model. Journal of Industrial Ecology 28, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13442

Ripple, W.J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T.M., Barnard, P., Moomaw, W.R., 2019. World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency. BioScience. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088

Tainter, J.A., 1990. The Collapse of Complex Societies, Reprint edition. ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire; New York.